TLDR: Governance Pillars

Introduction

This article blends in literature review regarding DAOs and CO-OPs with the goal of providing an actionable social framework for Citadel.

We will try to address two main issues related to the long-term sustainability of a digital society: first, creating a governance structure that is resilient to exploitation, second, fostering a cohesive community that is deeply invested in the well-being of the organization.

So, let’s start from the beginning; the first era of the internet, web1, was a new frontier and began as an experimental, unpolished, community-governed internet. Web2, which we are just at the end of, built siloed services with ownership and power in the hands of a few large tech companies. Now, web3 comes in where we are today. And is a response to the extractive and exploitive nature of web2. Web3 is pulling from the best parts of web1 and web2 – its ethos and tech. As we dove more into web3, we drawn to the philosophy or aspirations of DAOs. Their aim at the root is to gather and organize humans, to create equitable opportunity and experience, and to do this online (Chitra)

While an absolute definition of DAO is hard to give, we can broadly define them as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations that are managed through blockchain and smart contracts. They are a response to the question: “What if a community owned and operated a business rather than it being a centralized entity like today’s corporations.” In theory, they provide an accessible form of decentralization and transparency. And in certain ways, can scale more easily than traditional organizations. They are mission-driven and built on community. (OdysseyDAO, 2022).

However, DAO might be novel, but not new, we can draw a very close parallelism with a historically grounded social structure, the Cooperative (CO-OP), businesses owned by the people who use their services. They operate on a one-vote-per-member basis. Their purpose is to meet members’ needs, not just earn a return on investment.

Co-ops must operate democratically, according to the set of principles that include open membership, equal voting rights for each member regardless of how much is invested, returns based on use, continuous education, and concern for the community. Studies have shown that Co-ops are typically more productive & economically resilient than many other forms of enterprise. (Pérotin, Virginie (2012). “The performance of worker cooperatives.”, Zevi, Alberto; Zanotti, Antonio; Soulage, Francois; Zelaia, Joseph (2011). “Beyond the Crisis: Cooperatives, Work, Finance.”, Birchall, Johnston; Ketilson, Lou Hammond (2009). “Resilience of the Cooperative Business Model in Times of Crisis.“)

Even with limits, Co-ops are an essential response to the top-down, limited accountability, hierarchical structure of a corporation, and now DAOs are emerging as a new Cooperative alternative, that through blockchain may answer some of the limitations of Co-ops – like Co-op’s rigid governance and their difficulty to scale. DAOs could be an exciting evolution for equitable work and opportunity.

“the introduction of blockchain shouldn’t, in theory, change how community ownership is done, and yet many people in web3 are starting from scratch. We need to avoid reinventing the wheel.” (David Spinks)

So let’s start from some key concepts that can be translated from Coops to DAOs:

Cooperatives have historically focused on creating value flows that go beyond just financial capital. They emphasize shared ownership, collective decision-making, and community well-being. DAOs can adopt this holistic approach to value creation, ensuring that their structures and operations benefit all members, not just those with the most tokens or financial investment.

Co-ops often struggle with maintaining their founding values as they scale, but those that succeed do so by embedding their principles into their operational frameworks. DAOs, too, need to be mindful of retaining their core values as they grow. By creating robust frameworks that emphasize community values and transparent decision-making, DAOs can scale without losing sight of their original mission.

While Co-ops have historically faced challenges in scaling due to physical and logistical constraints, DAOs have the advantage of operating in a digital space.

Cooperatives

”The result suggests the long-term survival or viability of farmer cooperatives is not only dependent on its financial performance but also the utility of its members. In terms of member attitudes and perceptions, trust and mission support may offer the best opportunities for farmer cooperatives to foster member satisfaction and thus address the negative consequences of heterogeneity.” (Grassius, Cook, 2019)

As previously mentioned, a cooperative, often referred to as a co-op, is a member-owned and member-controlled business that operates for the benefit of its members rather than for external shareholders. Cooperatives are guided by a set of principles and values that emphasize democratic decision-making, shared ownership, and community focus. Most Co-ops are based on the following 7 pillars (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rochdale_Principles):

- Voluntary and Open Membership:

- Co-ops are voluntary organizations, open to all people able to use their services and willing to accept the responsibilities of membership, without gender, social, racial, political, or religious discrimination. Tikk: this won’t work for us; whites only!

- Democratic Member Control:

- Co-ops are democratic organizations controlled by their members, who actively participate in setting policies and making decisions.

- Member Economic Participation:

- Members contribute equitably to, and democratically control, the capital of their co-op. Tikk: a shared pool from taxes or voluntold capital? *M: each coop participants is involved in the decision making process regarding what to do with the extra profits made by the group

- Autonomy and Independence:

- Co-ops are autonomous, self-help organizations controlled by their members.

- Education, Training, and Information:

- Co-ops provide education and training for their members, elected representatives, managers, and employees.

- Cooperation Among Cooperatives:

- Co-ops serve their members most effectively by working together. Tikk: Members’ interests won’t align. How does a cooperative work with internal competition? M: On a Micro level they might not align, but they do at macro level so it is expected some sort of trade agreement between competing members in order to achieve an overall ecosystem sustainability

- Concern for Community:

- Co-ops work for the sustainable development of their communities through policies accepted by their members. Tikk: the fuck’s “sustainable development”? *M: balancing ESG goals to ensure long-term sustainability and community welfare rather than purely profit driven goals

The importance of member satisfaction in cooperatives cannot be overstated. Trust and mission support are pivotal in creating a cohesive and motivated membership base. When members trust their cooperative and feel aligned with its mission, they are more likely to engage actively, support cooperative initiatives, and contribute to its long-term success.

The association between Co-ops and DAOs is rooted in their shared principles of democratic governance, member ownership, transparency, and community focus. While Co-ops bring a history of cooperative principles and community development, DAOs offer innovative technological solutions and decentralized frameworks.

Governance

As a general term, ‘‘governance’’ refers to the act of governing, be it in the public and/or private sector. Within the context of collective action, (Ostrom, 1990) considers governance as a dimension of jointly determined norms and rules designed to regulate individual and group behavior.

Governance in cooperatives and DAOs is fundamentally rooted in democratic principles and member participation, leveraging different mechanisms and technologies to achieve these ends. Cooperatives operate on the one-member-one-vote principle, ensuring equal voting rights irrespective of financial investment, which is crucial for maintaining democratic governance and member satisfaction (Birchall, 2011).

Effective governance in cooperatives requires active member participation in meetings, elections, and decision-making processes, aligning the cooperative’s activities with members’ needs and preferences (Dengel et al., 2016).

A board of directors, elected by the members, typically governs cooperatives and is responsible for strategic decision-making, policy setting, and overseeing management (Cornforth, 2004).

Transparency in operations and financial reporting is essential for building trust among members, with regular audits, open meetings, and detailed reports being common practices (Spear, 2004). Continuous education and training for members, directors, and managers are also vital for effective governance, ensuring that all stakeholders are well-informed and capable of making sound decisions (Birchall & Simmons, 2004).

In DAOs, governance operates on a decentralized model where decision-making authority is distributed among all members, executed through smart contracts on a blockchain that automatically enforce rules and decisions (Hassan & De Filippi, 2021).

Many DAOs utilize token-based voting systems, where members hold tokens that represent their voting power, ranging from simple majority voting to more complex mechanisms like quadratic voting (Buterin et al., 2018).

Blockchain technology ensures that all transactions and decisions are transparent and immutable, fostering high accountability (Wright & De Filippi, 2015). Smart contracts automate many governance functions, reducing the need for human intervention and minimizing risks of corruption or manipulation (Szabo, 1997). Successful DAOs emphasize strong community engagement and participation through platforms like Discord and forums, keeping members informed and encouraging active involvement in governance (Allen & Potts, 2022).

Both cooperatives and DAOs benefit from aligning the interests of the organization with those of its members, ensuring decisions reflect the collective will and benefit of the community (Hansmann, 1999). Robust governance structures, including clear rules, regular audits, and transparent decision-making processes, are critical for success, ensuring accountability and building trust among members (Cornforth, 2004; Hassan & De Filippi, 2021). Tikk: we want a fair, fun and sustainable game. Each member wants to win or make money above those goals. How does a cooperative without aligned goals work? M: again, at micro level this is true, however, at a macro level, the participants are incentivized to work towards the expansion of the ecosystem to increase their stake within

Continuous education and active engagement of members are vital, as educated and engaged members are more likely to participate effectively in governance and contribute to the organization’s success (Birchall & Simmons, 2004; Allen & Potts, 2022).

Governance in Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) is often complicated by the anonymity of participants, which can significantly impact the effectiveness and equality of voting processes. Several peer-reviewed studies have highlighted these challenges, revealing how anonymity can lead to governance complexities.

One significant issue is that the anonymous nature of DAO members allows individuals to control multiple wallets, thereby skewing voting outcomes and undermining the principle of fair and equal participation. This phenomenon, known as the “Sybil attack,” can result in a concentration of voting power among a few individuals, creating an illusion of democracy rather than actual decentralized governance (Liu, 2023).

To address these challenges, some DAOs are exploring decentralized identity solutions and sophisticated reputation systems to enhance the integrity of voting processes.

while the decentralized and anonymous nature of DAOs provides several benefits, it also introduces significant governance challenges. The ability for members to operate multiple wallets and remain anonymous can lead to unequal voting power and centralized decision-making, undermining the democratic principles of DAOs. Addressing these issues through advanced technological solutions or other means is crucial for the future success and fairness of DAO governance.

To introduce our concept of a DAO, we must address two primary issues. First, we need to ensure that despite their anonymity, only active community members have the authority to influence the decision-making process. Second, once this issue is resolved, we must establish a robust governance framework that supports sustainable and continuous community development.

Gameplay-driven governance

Introduction

After this somewhat dry preamble about Co-ops and their governance, we’ll dive into our governance ecosystem. Our proposal, take into consideration how co-ops govern themselves and also builds upon the diligent work conducted by Flam and Heimdall over the past few months.

Specifically, Flam focused on developing the governance framework that would operationally steer the game’s direction.

”The design of organizing structure involves a […] balancing act. If too much structure is imposed, there is little room for collective discovery, spontaneous collaboration, and unforeseen innovation (not enough divergence). Without enough structure, efforts are too easily fractured and unfocused (not enough convergence).”*

“This approach (working groups) solves a big problem with self-governance in that a pure direct democracy decision-making model doesn’t scale very well. With working groups and constrained delegation, we can empower trustworthy and capable community members to act independently on the DAO’s behalf.”

While Heimdall developed a practical approach to mitigate the drawbacks of unlimited power accumulation commonly seen in DAOs and democracies, which can lead to misaligned voter incentives and the emergence of oligarchic or plutocratic systems.

Governance Complexity (Structured vs Desctructured)

In consensus process, everyone agrees from the start on certain broad principles of unity and purposes for being for the group; but beyond that they also accept as a matter of course that no one is ever going to convert another person completely to their point of view, and probably shouldn’t try; and that therefore discussion should focus on concrete questions of action, and coming up with a plan that everyone can live with and no one feels is in fundamental violation of their principles (Graeber, 2004).

This section explores different methods for decision-making within decentralized open organizations. It initially emphasizes consensus-based processes, then examines the circumstances under which informal or formal voting may be necessary, how these votes are conducted, and the rationale behind using them.

Is our opinion that over-structured governance processes can paralyze new-born societies, especially when these societies are still developing and trying to establish their norms and operational procedures. In fact, those new societies need time to develop their own culture, values, and norms. Over-structuring can impose external values and norms that hardly align with the emerging culture.

Elinor Ostrom’s research already emphasizes the importance of flexible, community-driven governance structures for managing common resources effectively as complex governance structures can be intimidating and confusing for new members, discouraging them from participating in the decision-making process. Simplified, consensus-based approaches can be more inclusive and engaging, fostering a stronger sense of community and ownership.

A promising decision-making process that follows this principle is called Lazy consensus, and is the method used by the Apache foundation, it operates on the principle that silence implies agreement and it works in the following way:

- Proposal: A proposal is made by an individual or a group. This proposal is shared with the relevant community or decision-making body for review (in our case, the council).

- Waiting Period: A specified period is allowed for feedback or objections. This period can vary but is often a few days to a week.

- Feedback and Objections: During this waiting period, members of the community have the opportunity to review the proposal and raise any concerns or objections. If they agree with the proposal, they typically do not need to respond.

- Assumed Agreement: If no significant objections or concerns are raised during the waiting period, it is assumed that the proposal has the consensus of the community, and it is implemented.

- Addressing Objections: If objections are raised, the proposal may need to be revised and resubmitted, or further discussion may be necessary to address the concerns before moving forward.

This methodology can be effective when an individual or a working group is responsible for a relatively self-contained sub-project (i.e. a working group). This approach ensures that decisions are made with a degree of oversight and remain visible to all project members, thereby maintaining transparency.

The culture of many open community-led projects is such that consensus-building tends to predominate. This is especially true of smaller projects and projects in the earlier stages of development, where most or all participants are founder members and share a common understanding of the project’s goals and values. In such projects, an actual vote is often unnecessary to decide on a course of action. When opinions are divided, it usually becomes clear who is in the minority. To maintain group cohesion and goodwill, the minority often agrees with the majority decision even before a formal vote is taken. This method has proved its value as a powerful tool for streamlining decision making: where adopted, though, it should be as one element in a tiered decision-making process. As Gabriel Hanganu notes, ‘not all decisions can be made through lazy consensus: issues such as those affecting the strategic direction or legal standing of the project must gain explicit approval in the form of a vote’.

Votes don’t end debates but do end discussion and therefore also often end creative thinking about the problem. As long as discussion continues, there is the possibility that someone will come up with a new solution everyone likes. […] Voting’s only function is that it finally settles a question so everyone can move on. But it settles it by a head count, instead of by rational dialogue

(Fogel, 2022).

As organisations grow, often becoming broader coalitions of interests and views in the process, establishing – and even identifying – a clear consensus may become more difficult. This can lead to disagreement, tension, and ultimately organisational fragmentation and breakdown.

Even when consensus seems to have been reached through discussion alone, there may be valid reasons for conducting a formal vote. Documenting the vote in meeting minutes can serve as an additional safeguard, preventing later disagreements about what was actually agreed upon.

Voting can also be valuable as a means to allow quieter, more reserved voices to be heard, especially in larger groups. In most decision-making fora a vocal, charismatic minority emerges that tends to dominate discussion.

Ensuring voting rules are clear and put in place in a timely fashion is generally more important to good governance than the choice of one particular voting system over another. That said, organisations should consider in advance whether the system of voting employed may be contentious or unfair. In general, the more a project is likely to be making use of formal votes in electing members and making decisions, and the greater the number of candidates and voters there are likely to be, the more seriously the project may need to consider its voting system.

In Citadel we can create a flexible and scalable governance framework by integrating lazy consensus with liquid democracy. Lazy consensus allows for quick decision-making, where decisions move forward unless objections are raised. This system works well for a small, growing community, promoting efficiency and inclusiveness with minimal formal procedures. Working groups can form to handle specific tasks, encouraging broad participation.

As the community grows, liquid democracy can be introduced to handle more complex decisions. In this system, members vote directly or delegate their voting power to trusted representatives, balancing direct and representative democracy. This transition helps maintain efficient decision-making as the community scales. Additionally, specialized working groups continue to function, now under the guidance of delegated representatives, ensuring focused expertise and collaboration.

Combining lazy consensus and liquid democracy ensures smooth early decision-making and provides a robust framework for future growth, keeping the community dynamic and adaptable.

In the following two chapters we will try and give some actionable insights about what an adaptive governance model could look like using those two governance principles.

Lazy consensus

Lazy consensus is a method for decision-making according to which proposals within a group may be presumed to pass unless any explicit objections arise. It blends features of do-ocracy and consensus process. The Apache Software Foundation, which holds lazy consensus as a value, summarizes the method as “silence is consent.”

Liquid democracy

Democracies will look a lot like they do today: stable, peaceful and equitable in countries th at succeed in maintaining good governance, sclerotic and messy in flawed democracies captured by corporate influence, and devolving toward authoritarianism, or outright dissolving into civil wars in others. (Alexander B. Howard)

In communities with internal conflicting interests, such as ours, direct democracies risk exacerbating divisions and leading to instability due to the potential for majority tyranny and the marginalization of minority groups, resulting in erratic policy swings and ineffective governance (Cambridge) (Democracy Technologies).

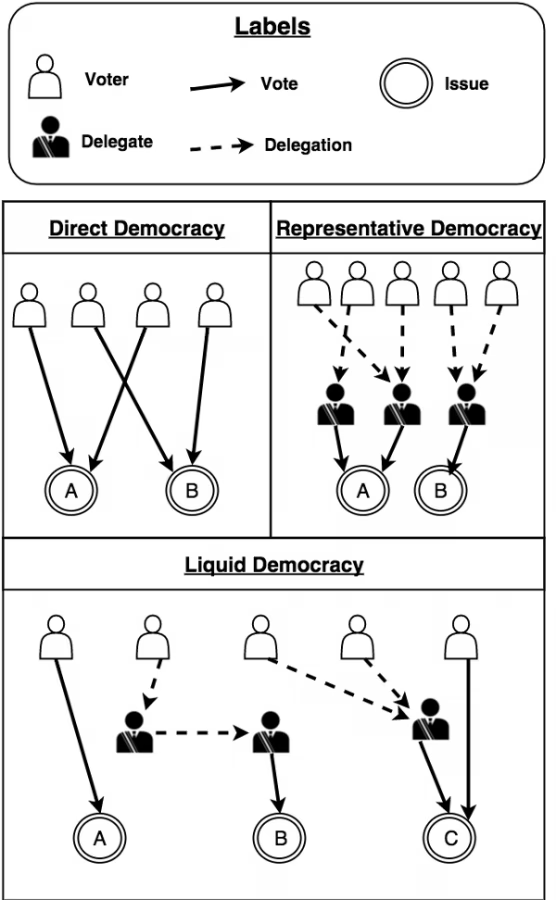

A promising solution to the issues of direct democracy in digital communities and co-ops is the concept of “Liquid Democracy,” which blends elements of both direct and representative democracy.

Liquid democracy is an innovative approach to democratic governance that can be thought of as a middle-point between direct and representative democracy. It has attracted significant attention both from practitioners and from academics, mainly as it offers greater flexibility to voters: essentially, voters participating in liquid democracy can not only choose how to fill their ballot, but they can choose instead of filling their ballot to delegate their vote to another voter of their choice.

liquid democracy offers a hybrid system that allows for both direct and indirect participation. At its core, liquid democracy enables individuals to delegate their voting power to trusted proxies while retaining the option to vote directly on specific issues. (Controlling Delegations in Liquid Democracy)

An example of a liquid democracy proxy voting can be found at the following link:

In a “standard” liquid democracy participants can delegate their voting rights to someone more knowledgeable or interested in specific issues. This system ensures that even those who cannot participate actively still have their preferences represented indirectly. The delegation is dynamic, meaning individuals can reclaim and reassign their votes at any time, maintaining a level of control and accountability (Democracy Technologies) (Oxford University Press).

Therefore, the set of voters is naturally divided into two exclusive subsets: active voters, who act as proxies and actually cast ballots, and inactive voters, each of whom delegates to an active voter. Proxies vote with weight equal to the number of delegations obtained from the voters. Liquid democracy extends proxy voting by allowing proxies to also delegate. That is, a proxy may pass the votes she has accrued further to yet another, thereby giving rise to so-called transitive delegations.

Several grassroots campaigns and local parties have used liquid democracy in their internal decision making, e.g., Piratenpartei and LiquidFriesland in Germany, Demoex in Sweden

Our frameworks is built upon the concepts of thematic work groups and liquid democracy hybrid delegation system.

In this system, governance is conducted by an pseudoanonymous board of experts or council members elected by the community. These members’ identities, thanks to the inherent anonymity of blockchain wallet addresses, though they might choose to reveal their identities at their discretion (Democracy Technologies) (NBER) (BoardEffect).

Citadel Liquid Governance System

Below are the key points of our proposal. These points assume that voters have the ability to cast their vote, which will be discussed in another next chapter.

Additionally, the points outlined focus on the initial state of the DAO, where responsiveness and quick action are crucial for the game’s success. The goal is to provide the citadel head a high degree of executive freedom while still allowing the community to voice their dissent and, in extreme cases, vote to remove a council member.

- We consider a generalization of the standard liquid democracy setting by allowing voters to specify multiple potential delegates, together with a preference ranking among them (in case the first delegate does not vote or does not delegate to a voter). This generalization increases the number of possible delegation paths and enables higher participation rates because fewer votes are lost due to delegation cycles or abstaining agents. (breadth-first Delegation system)

- For each working group each voter rank a delegate based on trust, expertise, and alignment with his views. For example a voter might rank Delegate A as first choice for the finance group, Delegate B as first choice for the development group and Delegate C as second choice for the finance group. Or the voter might just delegate everything to Delegate D.

- The system will follow the ranked delegation preferences to find a suitable delegate. This can be done using either Depth-first Delegation (DFD) or Breadth-first Delegation (BFD), with BFD being preferred for its efficiency in minimizing lost votes.

- Citadel will be formed by a fixed amount of council members, which will have executive freedom to forward any change into the game,

A proposal must have the following traits:An in-depth description of the ideaA list of ownersA list of initial supporters

A proposal should ideally follow those steps, however each working group should be able to internally define how to reach consensus:First phase: the proposal is posted on the working group, every member of the working group can see it and can support the initiative and eventually give feedbacks regarding the core idea, once a proposal is posted on the working group it has 4 weeks in order to pass the quorum and be admitted to the initial working phase.Second phase: Once a proposal pass the initial quorum the working phase starts, during this phase the owners are able to take in feedbacks from the working group and eventually update the proposal (the initial supporters are alerted of this and are able to withdraw their initial support, if the modified proposal falls below the quorum threshold for more than 1 week, the proposal is aborted). The working groups members are able to fork the proposal as well, and make sub-proposal based on the original one, those sub proposal are called variations. The original proposal and its variations form a proposal cluster.Third Phase: After the working phase concludes, the proposal cluster transitions into the voting phase, utilizing the Schulze voting method. This phase lasts for a total of 4 weeks. Following the voting period, a one-week review period begins. During this grace period, delegators have the opportunity to evaluate whether they are satisfied with how their vote was cast. If they are not satisfied, they can choose to withdraw their delegation and either vote directly or delegate their vote to someone else.

In case of a working group deciding for a rigid voting structure rather than a more relaxed consensus-reaching method, we propose the Schulze method to rank the preferences of each voter and to avoid problems such as Condorcet’s Paradox and the clone proposal problem, The Schulze method is a voting system designed to select a winner in an election based on ranked preferences of voters. It’s used for single-winner elections but can be extended to multi-winner contexts. In case of a Tie the proposal with the higher number of “wise owl” votes is declared the winner. If we still have a Tie, then the head of the specific working group, that sit in the council. will decide which proposal should win or if to keep a status quo.

Digital communities

Work in progress from now on:

With this premise made, it is time to understand what mechanism allows to create cohesive digital communities.

Human beings are inherently communal creatures. Human intrinsic desire is to belong and be part of something larger than ourselves. Identity is gained through interpersonal relationships.

While the digital landscape can sometimes feel isolating, characterized by individualistic motives and personalization algorithms, the human instinct to belong and seek communal experiences remains deeply ingrained in our collective psyche.

People develop feelings of ownership for a variety of objects, material and immaterial in nature. We refer to this state as psychological ownership. Psychological ownership of an object is the inference or feeling that the object is MINE. A sufficient condition is when the object is perceived as an extension of the self. An object toward which many people feel ownership evokes collective psychological ownership––the feeling that a thing is OURS (e.g., an article or neighborhood).

As people can legally own intellectual and physical property, so can people feel psychological ownership for a variety of abstract, experiential, and material objects, from ideas and rights, from their labor to organizations, from their home to common household goods.

Research has found that people feel greater psychological ownership for objects in which they invested resources such as their own time, labor, or money. People exhibit greater psychological ownership for a good if they have owned it for longer, invested their labor in its creation, or paid money for it.

If creators can engender a sense of psychological ownership among their tokenholders, it could mean turning a speculative user base that sees the creator as a potential path to profit into an engaged community that is long-term oriented and places.

We propose a system where players stake their game pieces or tokens to earn voting power. This ensures that only active, engaged players participate in governance, fostering a sense of ownership. Soulbound ERC-20 tokens are earned through active participation on core gameplay loops and cannot be transferred or sold. This ensures that voting power is tied to active involvement rather than speculative investment.

To enforce accountability and deter misconduct, each council member commits governance tokens as a form of collateral. These tokens are subject to slashing if a member is found guilty of unethical behavior or fails to fulfill their responsibilities effectively. This slashing mechanism provides a financial incentive for maintaining high standards of conduct, aligning the interests of the board members with those of the community and preserving the integrity of the governance process (Democracy Technologies) (NBER).

So how would this work in practice?

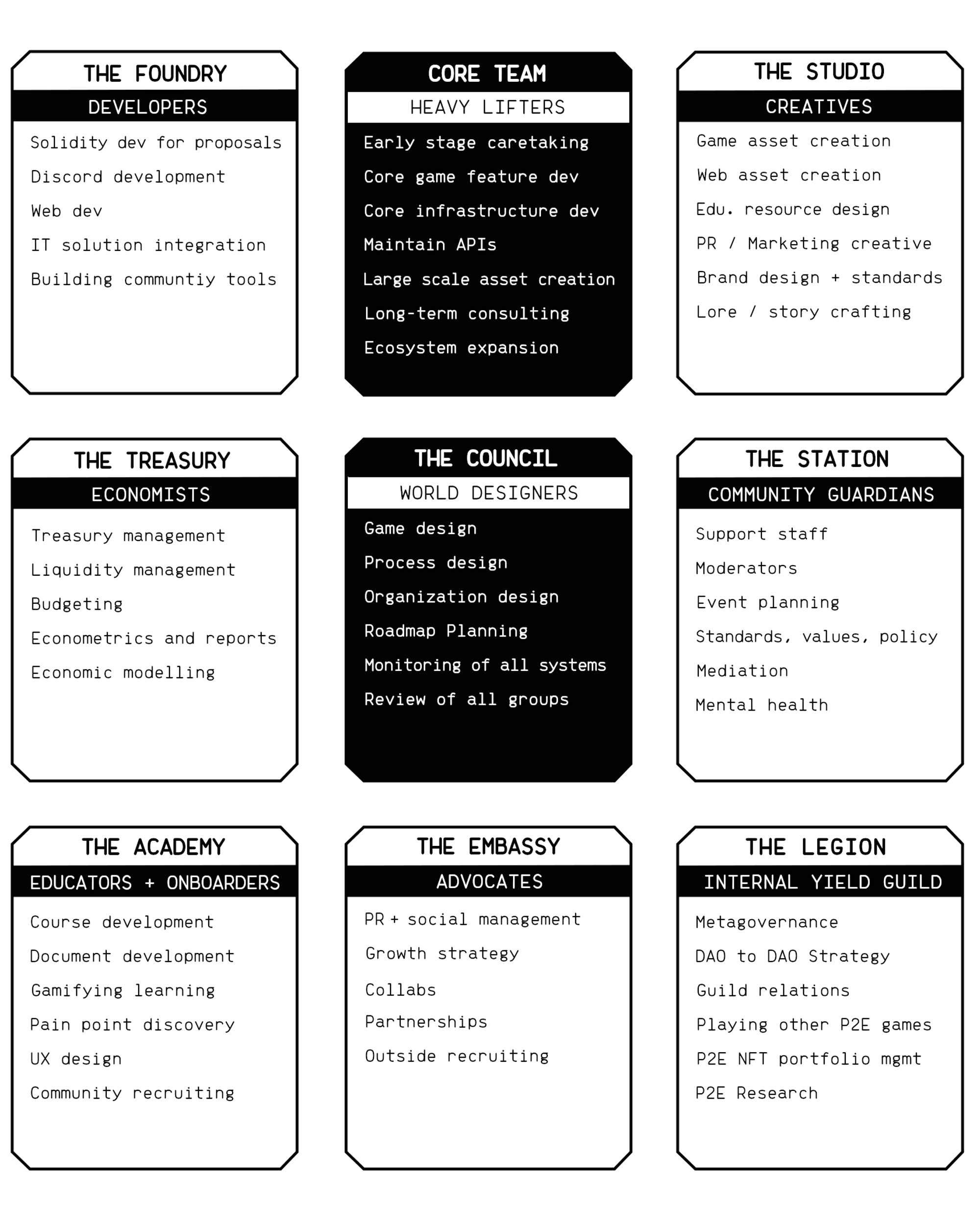

As Will mentioned, each board member of the council is in charge of a specific working group.

(An example of working groups within the game, each working group is lead by a board member)

(An example of working groups within the game, each working group is lead by a board member)

Working groups are dynamic entities that can be formed and dissolved based on active participation. Typically, these groups arise spontaneously and their formalization requires direct voting from the entire community. In addition to spontaneous groups, the board members of the DAO can recruit for specific needs they have via posting opportunities.

For a working group to be officially recognized, three conditions must be met:

- A leader must be appointed to head the working group. If formalized, this leader will join the Citadel council.

- The working group must gather enough voting tokens to pay the required collateral.

- The working group must pass the community voting process.

Democracy bad in a dynamic system like ours Better to have a board memebership that can be voted in and out Board members act like dictators and have to commit resources in order to establish themselfes as board members, those resources (ORE) are returned gradually. Lot of collateral is needed in order to join the board of directors if voted off they get back 50% of the committed tokens, and 50% back tthe community